Can money buy happiness?

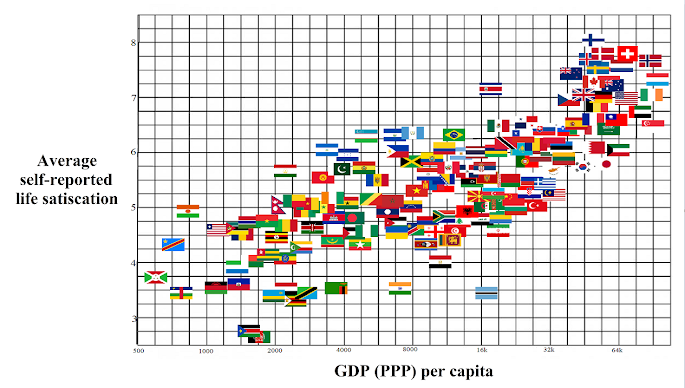

This scatterplot, based on data from the World Happiness Report, attempts to answer that question. And as you can see, the answer is... yeah, pretty much. The correlation is quite strong here, and it seems pretty likely that in this case correlation is a result of causation. The World Happiness Report (WHR) asks a representative sample of each country's population to rate their life satisfaction on a scale of 1-10. The poorest countries consistently have the lowest average scores, for obvious reasons. I don't need to spend much time explaining why people who wake up each morning not knowing whether they'll get to eat today might understandably report more than a bit of dissatisfaction with their lives. This scatterplot indicates that the better-off people are materially, the better-off they are psychologically. Happiness scores increase the higher a country's income gets.

That's all fairly obvious, however. What's more interesting to look at are the outliers--the countries located above or below the general trend line, whose happiness is considerably higher or lower than their income would suggest. Countries that are surprisingly happy in spite of their (relative) poverty include Tajikistan, Krgyzstan, Uzbekistan, Pakistan, Guatemala, Honduras, El Salvador, Nicaragua, Costa Rica, Panama, Mexico, and Brazil. On the flip side, countries who stand out for their relative misery include Bahrain, the UAE, Singapore, Japan, South Korea, Iran, Sri Lanka, Eswatini, Botswana, India, Egypt, Zimbabwe, Zambia, and Tanzania.

There are some interesting patterns to be found in the outlier countries. Two very different regions stand out for being positive outliers: Central America and Central Asia. This will probably come as a surprise to most Americans. We often associate Central America with poverty, drug trafficking, gang violence, mass migration, hurricanes, brutal banana plantations, and US-backed dictatorships. Whenever Central America comes on the news, it's something depressing like this. And there's no doubt that life there can be quite miserable, given how many people have been attempting to flee to the US in recent years. But clearly, there are also some factors that distinguish Central America from other developing regions, causing people to be a bit more satisfied with their lives. Honduras ranks just 138th in the world in terms of GDP per capita, but 56th in terms of happiness. Nicaragua 135th in income and 46th for happiness; El Salvador 118th and 34th; Guatemala 115th and 29th; Panama 53rd and 36th; Costa Rica 61st and 15th.

I can only speculate as to the reasons for this, but I can't help but think it's related to cultural values above all else. Perhaps there's a more laid-back outlook on life, more emphasis on relaxation rather than work, deeper friendships, stronger family connections, or perhaps a stigma around complaining that led to WHR respondants reporting higher levels of life satisfaction than they truly feel. It's also noteworthy that not all of Central America lives in crushing poverty--Panama and Costa Rica are relatively stable and prosperous. While Panama's self-reported life satisfaction is more or less what you'd expect based on their income, Costa Rica scores perhaps more impressively than anywhere else, ranking as the second- happiest country in America, just barely behind Canada and a good bit ahead of the US despite having only 1/6th of the GDP per capita. In the 1980s, Costa Rica abolished its military and instead spent the money strong social safety net, giving it better education, sanitation, and healthcare than anywhere else in Latin America. Costa Rican culture also likely plays a major role, placing an emphasis on relaxation and spending time with loved ones rather than grinding to get ahead (a concept they call "pura vida").

This cultural factor probably plays a role to some extent throughout Latin America, where the only country that falls well below the trend line is Venezuela, for reasons that should be obvious to anyone who reads the news. Everywhere else, people report a higher life satisfaction than other countries with a similar income. Perhaps the old stereotypes and cliches about the fun-loving, contented, lazy, laid-back Latino have a bit of truth to them. Or perhaps respondants exaggerated their life satisfaction in order to better fit that stereotype (a scientifically proven phenomenon). But most the most likely reason has to do with social support--a recent Gallup poll asked people whether they feel love and affection on a daily basis, and Latin America countries had among the highest percentages of "yes" responses. At the top of the list was a semi-Latino country in Asia--93% of Filipinos reported feeling loved, which provides a pretty clear explanation as to why the Philippines places well above the trend line.

On the opposite end of the spectrum, 14 of the 20 countries where the lowest percentage of people reported feeling loved were in the former Soviet Union. Why? I have no clue. There's certainly a stereotype of Russian having a cold and unfriendly exterior, but it has to go beyond cultural explanations--the USSR was a vast country that encompassed a wide variety of cultures. Central Asia and the Baltics have almost nothing in common besides having been under Soviet rule, yet in both regions very few people report feeling affection. This leads me to believe it's a cultural legacy of the Soviet Union itself.

Probably partly because of this, ex-Soviet countries generally do fall a bit below the trend line. In particular, Georgia and Armenia (which rank last and fourth-to-last in terms of feeling affection) are quite miserable. But still, the ex-Soviet countries aren't massive outliers like Costa Rica or Botswana. I must say, I sort of expected them to do worse. I'm prone to imagine that part of the world as being in a state of decay, gloom, and lack of meaning in a society hollowed out first by soulless communist beauraucrats and then by greedy capitalist oligarchs. But it's worth remembering that those communism also left a legacy of literacy, sanitation, infrastructure, and women's rights, so ex-Soviet countries actually have better living standards than their incomes would suggest. It's also worth remembering that the narrative of post-communist decay is also flawed, asmany ex-Soviet countries have developed considerably in the past three decades. The one country that has a lower GDP per capita than it did under the USSR is Ukraine, largely because of the war that's plagued the country for several years. As a result, Ukraine is a major negative outlier on the graph. Curiously, its neighbor Moldova, the poorest country in Europe, is actually a bit above the trend line. Russia is below it, but not terribly so. In spite of their reputation for suicide, the Baltic States are only slightly less satisfied than would be expected based on their relatively high incomes.

Since it has many of the same factors (such as lack of affection) that afflict other ex-Soviet states, it would be reasonable to assume that Central Asia, which is the poorest part of the former USSR, would be miserable. But no--it's the other major region alongside Central America where we can see a pattern of greater hapiness than income would predict. Westerners whose only exposure has been through the movie Borat associate Central Asia with cultural backwardness, misogyny, bride-kidnapping, terrorism, vainglorious dictators, depressing Soviet architecture, and poverty. This view is wildly off the mark, off course, as Central Asia countries are generally more secular and progressive than the rest of the Muslim world, and they vary widely in income--Kazakhstan is quite wealthy, while Krgyzstan and Tajikistan are rather poor but score quite decently on the WHR. Perhaps one reason is because they aren't as poor as their GDP per capita suggests: one Tajik explained to me that the Soviet legacy of social support is a major factor in bettering their lives.

Moving to the negative outliers, Botswana is the first one to jump out visually. I must say, this made me rather sad. Botswana is often touted as the success story of Africa, with one of the highest average incomes on the continent and a government that's remained stable and democratic since independence. And yet it ranked near the bottom of the WHR, indicating that perhaps this is a facade, as GDP numbers mask the country's deep inequality. And this may be somewhat true: according to a 2018 report, Botswana ranks 83rd of 149 on the Prosperity Index but only 134th of 149 in terms of standard of living. Another factor may be that a whopping 38% of Botswanans have HIV/AIDs.

Two negative outliers that did not surprise me in the slightest are South Korea and Japan, two rich countries that don't appear particularly happy. The popular image of Japan among non-weeb Westerners is a place of drone-like office workers overworked to the point of suicide.

The behemoth that is India also fared embarassingly badly on the WHR, reporting the ninth-lowest average level of life satisfaction in the world at just 3.573 out of 10. The poverty and awful living conditions that afflict much of the population are certainly a factor--the slums many Indians live in seem like a perfect breeding group for misery--but they aren't a sufficient explanation, as most countries with a similar GDP per capita fare considerably better. It isn't a matter of misleading GDP numbers, as India's other development indicators (life expectancy, education, nutrition, etc) are quite typical for a lower-middle-income country. It's something more.

My armchair analysis, which you ought to take with a massive grain of salt, is that this has to do with Hinduism and the caste system. The WHR explains its methodology as such: "Nationally representative samples of respondents are asked to think of a ladder, with the best possible life for them being a 10, and the worst possible life being a 0. They are then asked to rate their own current lives on that 0 to 10 scale." The entire purpose of India's millenia-old caste system is to do precisely this--rank how good people's lives are and provide a justification as to why some people wound up better off then others. Perhaps this somewhat formalizes Indian Hindus' analysis of their own lot in life--most people born into a lower caste see their current life as a misfortune to be overcome in order to place in a higher caste in the next life. Then again, only 40% of Indian Hindus believe in reincarnation according to a recent poll. Then again again, that's still a ton of people. Regardless, all this is pure speculation on my part.

But it does tie in quite nicely with a major topic I've been avoiding: religiosity. "The majority of well-conducted studies," reports a meta-analysis by the National Library of Medicine, "found that higher levels of religious involvement are positively associated with indicators of psychological well-being (life satisfaction, happiness, positive affect, and higher morale) and with less depression, suicidal thoughts and behavior, drug/alcohol use/abuse." It's not hard to understand why--believing that there's a benevolent God who will make everything okay in the end would logically make someone feel much better about life's troubles.

Going by the WHR, however, there's actually a negative correlation between religiosity and life satisfaction. The reasons for this are fairly obvious--poor countries tend to be far more religious, and the psychological benefits of religion aren't nearly enough to alleviate the misery of extreme poverty. That's reasonable enough, right? But I find it strange that religion seems to have absolutely no effect. In fact, the religious countries that are rich, like Saudi Arabia, actually place well below the trend line. And some of the most secular countries, notably Scandinavia, rank at the absolute top. Perhaps there's something of a discrepancy between happiness and life satisfaction--the hope of an afterlife doesn't do much to make people more satisfied with this life.

So in sum, there are lots of interesting insights to be found in this graph. Perhaps the least interesting is that there's a correlation between wealth and happiness. In spite of this, however, I still sorta agree with the saying "money can't buy happiness" in the context in which it's typically used. Obviously, it's hard to be happy if you don't know where your next meal is coming from, so for poor people, money very much is the key to being less miserable. However, money is really only valuable to your well-being insofar as it gets you a comfortable life. Someone who makes $150,000 a year will most likely have all the material prerequisites to live well, so they'll probably be more or less equally happy to someone who makes $1,000,000 a year--possibly even more so if they work less for that money.

Source for income:

https://www.gapminder.org/tools/#$model$markers$bar$encoding$x$data$concept=income_per_person_gdppercapita_ppp_inflation_adjusted&space@=country&=time;;&scale$domain:null&type:null&zoomed:null;;;;;;&chart-type=barrank&url=v1

Source for life satisfaction:

https://worldhappiness.report/ed/2020/social-environments-for-world-happiness/

Comments

Post a Comment